Why are magnetic components used in DC/DC converters? What are we trying to control when selecting these components and how do we know we’re selecting the right component?

We’re glad you asked these questions.

When initially writing this article, we wanted to go over all the types of magnetic components. As writing progressed, we decided specifically to focus on inductors and some of the intuition and thought that is often overlooked or misunderstood.

Inductors

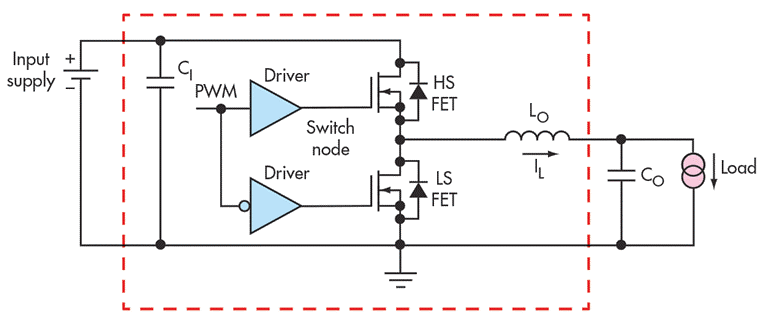

Inductors are passive components that consist of a conductor wrapped around a magnetic core. In the case of switching converter, the inductor is tied to a point called the switch node. The switch node is the place where an inductor, FET, and diode / synchronous FET are tied at a single point.

The inductor follows a simple equation:

V = L di/dt

Essentially, the current rate of change in an inductor ( di/dt ) is proportional to the voltage divided by the inductance. If you do the work to calculate current, you’ll realize that it’s proportional to the voltage and inductance of the inductor integrated over time.

Why is this useful in a DC/DC converter? For example, in a buck converter, the voltage is stepped down from some input voltage Vin to a lower voltage Vout. The way the buck topology does this is by PWMing the input voltage and chopping it up. When chopping the input voltage at a duty cycle of D, you get the output voltage:

Vout = Vin * D

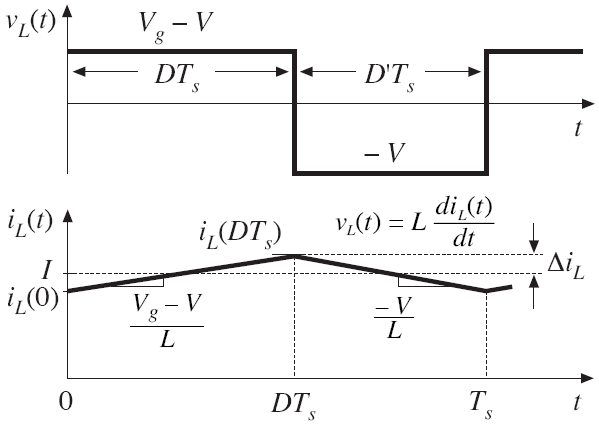

In the buck converter for example, the inductor is between the input source and the output. The duty cycle in the above equation references the portion of the time the high side (HS) FET is on, while the low side (LS) FET is off. During this time, a voltage of Vin – Vout is applied across this inductor. For the buck topology, the inductor current ramps at a rate of:

di/dt = (Vin – Vout) / L

When the converter is turning on the high side switch, current is ramping up in the buck converter’s output inductor. During this time, the converter is pulling energy from the input source and storing it in the magnetic field of the inductor.

Without thinking about this in terms of inductor current waveforms, you can think of the half-bridge (high side plus low side FET) of a buck converter as the structure that generates the PWM waveform. The switch node (where the high and low side FET meet) is then connected to an LC filter (output inductor and output capacitors). The LC filter attenuates the high frequency content to leave a mostly DC waveform at the output with some ripple.

Switching Frequency vs. Inductance

There is a trend in power electronics to increase the switching frequency of DC/DC converters, but what is the reasoning behind this trend? We mentioned that DC/DC converters take energy from the input source and perform some regulation to another voltage level at their output.

When designing a DC/DC converter, there is a goal to maintain regulation to a maximum output power (500W for example). The following equations show how we can think about a switching converter as transferring of packets of energy from the input source to the output (the operation isn’t 100% efficient and some will be lost in the process).

Power (W or J/s) = Energy per cycle (J) * switching frequency (s^-1)

500 W / 100 kHz = 5 mJ

If we increase this frequency to 200kHz, then the energy per cycle would decrease to 500 W / 200 kHz = 2.5 mJ. This is a reduction in energy per switching cycle by half. Reducing the energy per switching cycle means our energy storage components can be reduced in size.

This can be illustrated with the equation for the energy stored in a given inductor:

Einductor = 1/2 * L * I^2

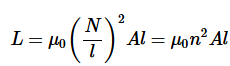

Since the quantities of voltage and current are fixed for a given output power, we can see that we are able to reduce inductance (L) proportionally. A reduction in the inductance of the converter means a smaller volume for these components since the inductance is proportional to number of turns squared ,cross sectional area, and length. The term A * l is the volume of the core material used.

The below equation illustrates the relationship between inductance

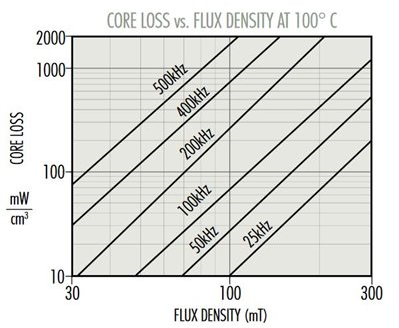

However, there are tradeoffs when pushing the switching frequency higher for a converter. For example, higher operating frequencies of magnetics mean higher core losses. The following graph is something one would typically see from a magnetic material used in inductors. For a given change in flux density, we can see that increasing the frequency causes a higher power loss per unit volume.

Some Limiting Factors

There are a few things to understand about inductors. If the current through the inductor (which generates a flux density) is too high, something called saturation occurs.

What is saturation?

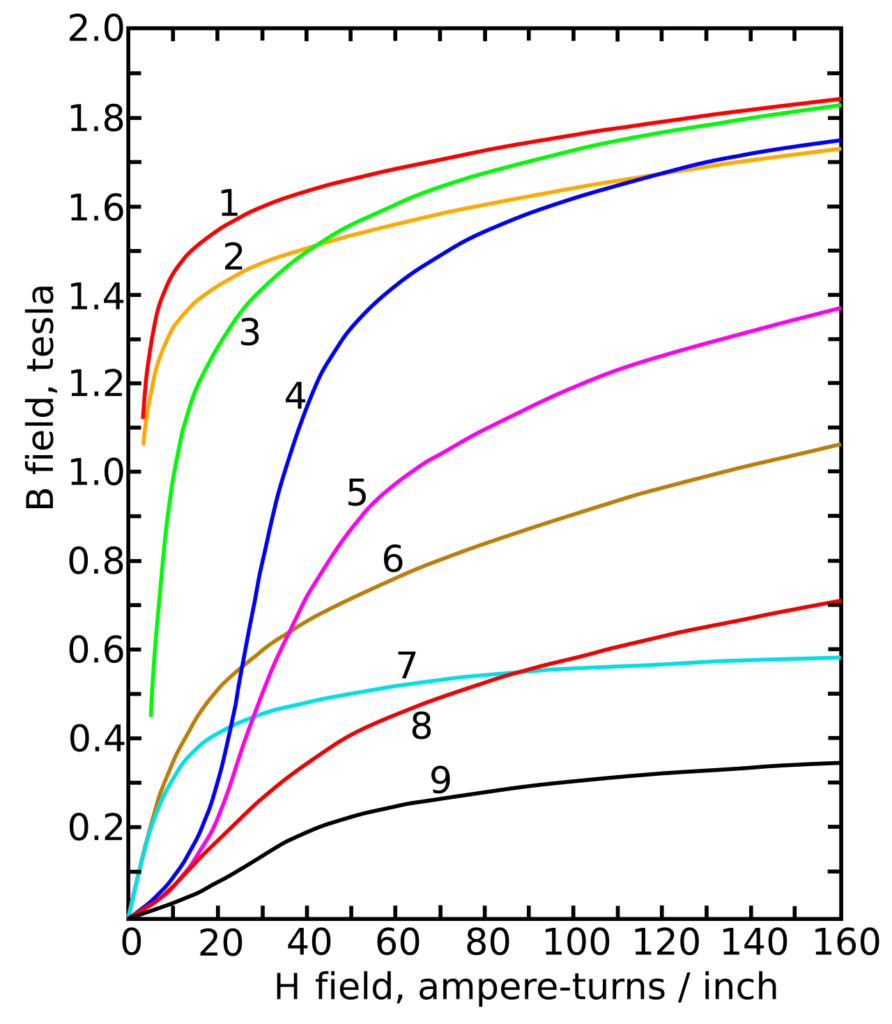

Saturation is when the increase in the magnetic field strength no longer causes the flux density to increase at the same rate it previously did along the BH curve. See the BH curve below for reference.

As the magnetic field strength continues to increase, the corresponding flux density will start to plateau. The magnetic permeability of a material is defined as the slope of B/H. The physical representation of this is that the relative permeability of the magnetic material starts to decrease with increasing H field.

When this curve is traversed to and beyond saturation, it’s as if the core material is transitioning from its original material and becoming more like an air core inductor and losing the properties of the core material.

Why is this a problem in a DC/DC converter?

As the inductor starts to enter saturation and it’s inductance drops (due to lowering permeability), the rate at which the current changes (di/dt) starts to increase. This can be seen in the equation for buck converter’s di/dt, which restated is di/dt = (Vin – Vout) / L.

Since di/dt is inversely proportional to L, as L decreases, the magnitude of di/dt increases.

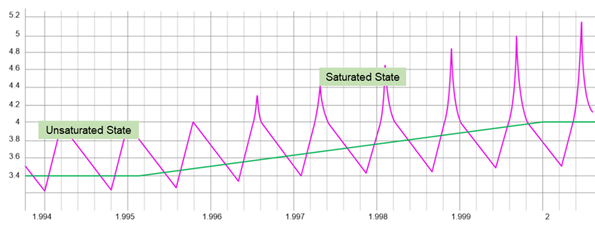

In most cases this is noticed when the current waveform changes from a triangular shape and starts to have a pronounced peaking. The image below shows what an engineer would see when watching an inductor go from an unsaturated state to a saturated state.

One problem with inductor saturation is the core material cannot store any additional energy, and the converter won’t be able to regulate the output.

Summary

Magnetics in switching converters are the backbone of traditional topologies. Understanding how to properly select materials, values, and the impact on the overall design is crucial to reliable operation of you hardware. This article went over a few of the ways in which inductors are used in switching converters and some of the pitfalls when designing.

The last thing you want to do as a product designer is guess on the implementation or neglect the nuances of your application. If you have a design that you don’t want to leave to chance, reach out to BuildEmber for a design consultation.

Need help with electronics design and software development? Reach out to BuildEmber for a consultation at contact@buildember.com or 832-391-5516.

No responses yet